But whereas Brecht's doggedly amoral Courage survived the Thirty Years' War through her willingness to play a multitude of roles in it, Birahima can only be one thing: a child solider. Birhahima is given an AK-47, a supply of dope, and orders to kill.įrom the moment Birahima picks up his gun, the story becomes a picaresque he remakes himself as a sort of child-soldier Mother Courage in order to stay alive. But once across the border, he quickly finds himself caught up in the tribal war raging there. Traveling from his home village in Cote d'Ivoire, he goes in search of his aunt's house in Liberia, hoping she will adopt him.

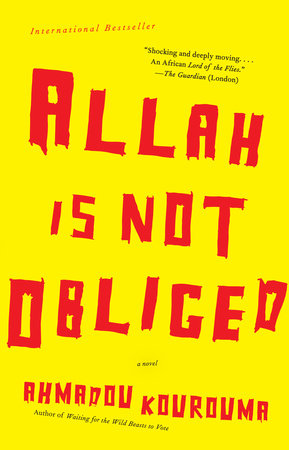

While his earlier work, including the novels The Suns of Independence and Waiting for the Wild Beasts to Vote, also covered criminality in postcolonial West African life, with Allah Is Not Obliged Kourouma takes aim at a more recent and jarring phenomenon in the region: the widespread use of child soldiers, whom he calls “the most famous celebrities of the late twentieth century.” The reader accompanies the narrator, a foul-mouthed ten-year-old orphan named Birahima, as he bounces from conflict to conflict over the course of several months in 1993. The novel, originally published in France in 2000, was Kourouma's last before his death in 2003. But because Kourouma sets his story in the middle of the civil wars that burnt through Liberia and Sierra Leone in the nineties, the characters' similarities are more apparent than their differences-everyone is equally corrupt, violent, and power-hungry. Ivorian writer Ahmadou Kourouma's Allah is Not Obliged abounds with characters who strictly define and divide themselves as Muslim, Christian, or animist. In the middle of the desert, baser appetites superceded religious beliefs. They were Muslim, surely, but at that moment a Dunhill held more appeal than prostrations and murmured Arabic. The sun was just starting to set, and the man sitting next to me said solemnly, “It's time for prayers.” As we all shuffled off the bus, he threw his arm around the shoulders of the man sitting across the aisle and said, “Come on friend, let's go pray.” As most of the other riders laid out their prayer mats facing east, however, the man and a group of his friends leaned against the bus and lit up a long line of cigarettes. I was on a bus in Mali, somewhere in the desert between Bamako and Ségou, when we suddenly lurched to a stop.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)